Innocence Lost: Surviving Sam Otts and His Dark Legacy

To most folks in Hot Springs, Ark., Sam Otts was a well-spoken bachelor with an aptitude for mathematics and a passion for scouting. When he wasn’t working at the local Salvation Army in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he was supervising the children in Troop 16 as their scoutmaster. His prematurely white hair made him seem almost grandfatherly, despite the fact that he was barely 50.

But to many of the young boys in his care, Sam Otts was not the paternalistic figure he seemed. He was a predator.

The Boy Scouts of America kept records detailing Otts’ history of sexually abusing children in a folder — one of thousands of such folders known collectively as the “perversion files” — even as they kept residents of Hot Springs in the dark about Otts’ true nature. The files show that Otts had previously taught at a boarding school in Floyd County, Ga., and served as local scoutmaster until 1977, when he was fired for sexually abusing the child of another faculty member. Instead of banning him from ever participating in boy scouts again — as one scouting official requested upon learning of Otts’ activities in Georgia — this pedophile was put in charge of Troop 16 and multiple scout packs after moving to Hot Springs.

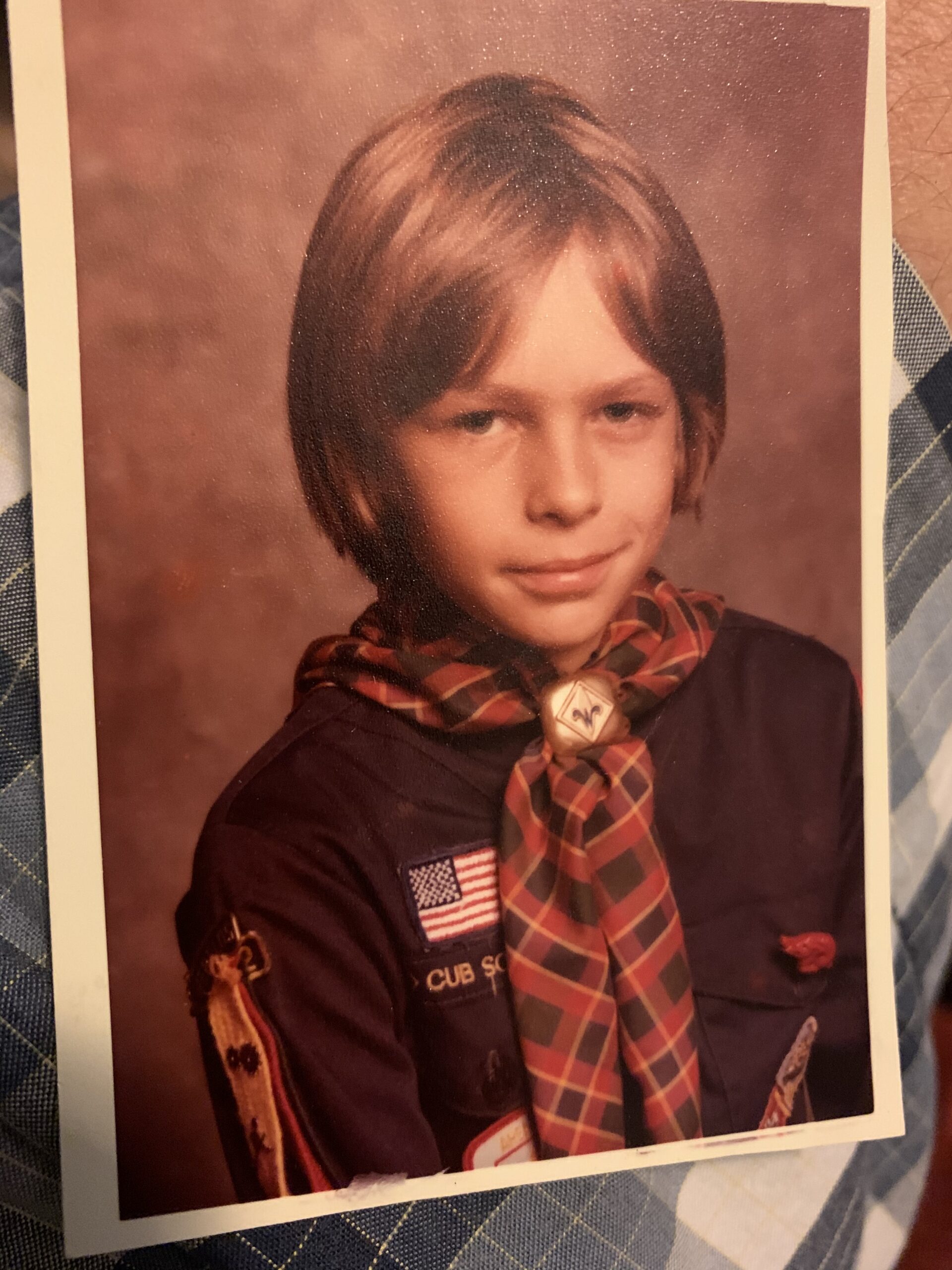

“Sam Otts, in center with white hair and mustache.”

In the wake of a new Arkansas law empowering sexual assault survivors to sue their assailants even decades after the statute of limitations has expired, several of Otts’ victims agreed to share their stories in hopes of encouraging other survivors of sexual abuse to step forward.

Skip

William “Skip” Goodrum III vividly remembers his first encounter with Otts. It was June 1980. The Hot Springs native was in his fourth year of cub scouts and attending a day camp held at the local school. The activities were being supervised by boy scout troop leaders, including Otts.

“He gravitated to me pretty quickly,” the 51-year-old Goodrum recalls. “I don’t know why he singled me out specifically. Maybe because I was extremely naïve and he sensed that.”

Goodrum remembers Otts would isolate him from the others, such as taking him behind a cluster of trees to show him how to tie a rope, and then rub his shoulders while the young Goodrum practiced. “I didn’t think much of it at the time … he seemed like a nice old guy.”

Otts’ sexual advances escalated when he started taking Goodrum and other cub scouts on camping trips that summer. Goodrum recalls Otts taking them to Camp Maurice, a largely disused campground. Due to the muggy summer heat and the heavy canvas used in the tents back then, the interior of the tents was like a sauna. It didn’t take much in that stifling heat for Otts to convince the boys to sleep naked on top of their sleeping bags. “I thought it was bizarre, but he was a senior scout leader telling me what to do, so I did it,” Goodrum remembers. Otts molested him and another boy that night — one who still has yet to come forward — and this cycle of abuse continued for nearly every weekend between June and August of 1980.

“I didn’t tell mom about it,” Goodrum says. “I couldn’t really process it.”

Otts’ abuse only came out by chance: a passing question from Goodrum’s grandmother about his most recent camping trip prompted him to tell her they had been sleeping in the nude, and further questioning from the family laid bare the awful truth.

“They got pretty upset,” Goodrum remembers. “It was then that it dawned on me that this was really bad stuff he’d done to me.”

His parents swore him to silence and told him to forget about his experiences, because “you didn’t talk about that stuff back then.” Both his parents and grandparents refused to ever discuss the matter again.

The psychological scars of Goodrum’s experiences and being forced to keep his pain bottled up inside manifested early.

“Mostly it was the rage,” he remembers. “I got into a lot of fights at school. I began drinking early and excessively.” As he got older, this graduated to public intoxication, bar brawls and experimenting with drugs. “I was like a bomb ready to go off.”

It wasn’t until Goodrum sought counseling at his second wife’s behest that he realized just how bad things had gotten. “It’s really helped,” he said. “I have anxiety, [post-traumatic stress disorder] and depression.” Once he committed to counselling, “things started to get better. The drugs stopped, the alcohol abuse stopped. … I started to unburden myself. It felt cathartic.”

The IT worker never found out what happened to his abuser. Otts disappeared quite suddenly from Hot Springs in August 1980 and all of Goodrum’s efforts to track him down have been in vain. Not even a death certificate exists for the man.

“It was like he just vanished one day,” Goodrum said. He thinks he knows why: His father wrote a letter to the boy scouts’ district council outlining Otts’ activities and demanding action. Goodrum first learned about the letter some 40 years later, when his attorney subpoenaed council records.

“That was a really good thing for me,” Goodrum says, noting he had been angry at his parents for years for seemingly refusing to address his victimization. “I honestly didn’t think my parents did anything” about the abuse. “You gotta have closure on things, and that was closure for me with my parents.”

Will

“Will”

But Otts didn’t vanish, as another one of his victims discovered to his horror in November or December of 1981. That was when William Stevens came face to face once again with the man who abused him and Skip, a year and a half after Otts had vanished from Hot Springs.

Stevens and his parents attended a speaking engagement hosted by their church and the Salvation Army, the same organization at which Otts had worked while in Hot Springs. During the function, Otts appeared in his Salvation Army uniform and walked up to the startled boy to give him a birthday card filled with quarters. Then he leaned over and whispered in Stevens’ ear the same line he’d used to groom the boy more than two years earlier: “you’re so very special.”

That was the last time he ever saw his abuser, though he learned years later through Internet sleuthing that Otts had moved to Oklahoma, with his last known address being a Salvation Army post in Ponca City. The trail ran cold after that.

“He was just moved to a different city,” Stevens says with palpable bitterness.

Stevens, a 52-year-old human resources professional who lives in central Arkansas, had joined cub scouts in 1978. The then-nine-year-old saw it as an opportunity to enjoy the great outdoors. “My parents were divorced and I wanted to do something more than sit around the house the whole time. … There was camping, fishing, and all the things a boy wanted to do.”

Stevens was quickly promoted to the Webelos Den of Cub Scouts in Hot Springs, which was overseen at the time by Otts. The abuse started in March of 1979, when Otts took a group including Stevens to Camp Maurice to camp out. “It was one of his favorite places to start his process” of abusing children, Stevens recalls.

“He wanted us all to sleep in our underwear, so we wouldn’t get too hot,” says Stevens. “I remember I woke up and he had put my hand in his armpit, and when I asked what he was doing, he told me I looked cold and this was how people kept each other warm in survival situations. Then he took my feet and placed them in his groin area. I told him ‘I’m not that cold,’ then turned around and went back to sleep.”

Otts continued his advances, using young Stevens’ desire to join the Order of the Arrow — a kind of honor society within the scouting organization — to prey on the boy. His abuse continued for more than a year, escalating in severity and frequency, and then stopped in the summer of 1980, a few weeks before boy scouts officials began questioning Otts on his interactions with the boys.

“I wanted to tell my parents … but they were bickering over custody [of Stevens in an acrimonious divorce], so I had no faith in my parents at that point in time,” Stevens recalls. Worse still, his father belonged to the same scout troop as Otts, and while his father had heard rumors of Otts’ misconduct, he had no idea his own son was one of the victims.

Stevens confided in his local pastor after he took Stevens and a number of other boys aside and asked them whether Otts had done anything inappropriate to them. One by one the boys said ‘no’ and left until Stevens was the last one. He recalls that the pastor took him by the shoulders and said “don’t lie to me.” Stevens told him what happened and was immediately sworn to secrecy, with his pastor assuring the boy that he would take care of it.

As a result of Otts’ abuse, Stevens retreated into himself. “The world expected you to go back to being a child again, but you can’t,” he explains. “My entire fifth grade year, I did … no homework all year. I just sat there in class and drew castles all day” in his notebook.

This behavior continued as he grew older, cutting off relationships on a whim to give himself the feeling of control. “I wasn’t that nice of a person,” he admits. “It was always there, the abuse, the anger, the shame. I felt like I was damaged goods.” He noted that he got into lots of fights, especially after he joined the military. “It cost me my military career, it cost me relationships, it cost me jobs,” he reflects. Stevens tried to deal with the pain in other destructive ways, including alcohol abuse and self cutting.

It wasn’t until he was in his late 20s that Stevens slowly tried to confront his demons. “I started writing poetry about everything,” he recalls. “I wrote down my feelings, and found that by doing that, I was able to process it. It was a form of self therapy.”

That’s not to say the pain is ever entirely gone. “I look at my eyes in pictures, before and then during and after” the abuse, Stevens says. “And that little spark of that little boy isn’t there anymore. I sometimes look in the mirror now for that spark to see if it will ever come back, but I don’t think it will.”

Jeff

“Jeff”

Unlike Goodrum and Stevens, Jeff Burfeind wasn’t a native of Hot Springs, having only moved to town from St. Charles, Mo., in 1978. That outsider status is what drew him to the cub scouts. “I joined mostly to make friends,” the 52-year-old recalls. Unfortunately, scouting was also his introduction to Otts.

Sometime in either 1978 or 1979, Otts took Burfeind and other Webelos on an overnight camping trip during which they fashioned loin cloths. Otts used this as an excuse to convince the boy to strip.

But the real abuse came later, when Otts entered the young Burfeind’s tent at night. He was sharing the tent with three other boys and Otts insisted that this was too many, and that one of them had to join Otts in his tent. Burfeind still remembers how the other children reacted. “Two of the other boys were literally clutching each other in fear. The third boy was staring at the ground to avoid eye contact” with Otts, Burfeind remembers. The young Burfeind was selected and recalls of his abuse: “I went catatonic, I just laid there. I couldn’t move, I couldn’t scream, I couldn’t do anything.”

That was the end of Burfeind’s participation in scouting. While he attended to a few more meetings following the abuse, he never got invested and he made sure he was never alone with Otts again.

“I tried to tell my parents. I dropped little hints but they didn’t pick up on them and I was way too embarrassed to even describe what happened to me,” recalls Burfeind, who now works as a phone technician in Florida.

Like the others, Burfeind still struggles with the pain of his experiences. “It affects me even today,” he admits. “I’m having problems with my daily life, with my finances, my work.”

In school, he refused to shower after P.E. class. As an adult, he still gets a knot in his stomach every time he uses a public restroom in the presence of others. And at the core of it all is an uncontrollable rage at the memory of his abuse.

“You can’t bury it and you can’t hide it,” he says. “It doesn’t go away. It will probably be the hardest thing you ever go through to talk about. I definitely recommend counselling.”

Burfeind didn’t know where to direct his frustrations until he stumbled on a social media post a few years ago from Stevens, who sued the Boy Scouts of America in 2018 for what they let Otts do to him and others. While the suit failed on the grounds that the statute of limitations had expired, seeing Stevens example inspired Burfeind to come forward.

Aftermath

Following Stevens failed attempt to hold the boy scouts accountable for Otts’ crimes, Arkansas passed a law — S.B. 676 — in April opening the floodgates for nearly 900 Arkansas men to sue the boy scouts and the various regional councils in the state. Goodrum, Stevens and Burfeind are among them.

“This law means a lot to me,” Burfeind says. “It means a lot because it’s going to protect children. And that’s what’s most important.”

Goodrum seconds that notion. “It gave us a chance to let our stories be told and expose all this horrible stuff that happened,” he says. “I didn’t get into this for the money … To me, this has all been about getting my story out. Get it out of my head and let people know about it.”

Stevens sees S.B. 676 — now designated Act 1036 after the governor signed it into law — as the culmination of his years-long effort to hold the boy scouts accountable for his victimization. When his lawsuit failed, he felt like “I didn’t matter. Throughout the entire process … I heard a 10-year-old version of myself screaming: ‘When did I ever matter?’ And I think when the bill was passed, it was the moment to know that we all matter. That we’re not just sexual prey.”

All three men recommend that victims of childhood sexual abuse seek help in dealing with the trauma.

“It’s unhealthy to keep that stuff bottled up,” Goodrum says. “You don’t have to make it public, but at least talk to someone about it. And if that person isn’t helping you, find someone who can.”

Burfeind agrees, noting that “talking about things makes you remember just how important this is.”

Stevens notes that while “coming forward may seem like the hardest thing you will ever do, it can actually be the most rewarding thing you’ve ever done. I can honestly say this: sharing my experiences … was the most meaningful thing I’ve ever done in my adult life.”